Which species should be classified as Humans?

We don't know if Neanderthals count as humans, or if chimps do, because we can't agree on the defining features of a human

Some say it is culture that makes us human. Others opt for our morality, language, or even our sense of humour. But putting philosophy to one side, what literally makes us human?

Surprisingly, there is no official answer. Science has yet to agree on a formal description for our genus, Homo, or our species, sapiens.

It's not for lack of trying. There are actually several suggested definitions for the human genus – and an astonishingly broad range of opinions over what does and does not belong within it.

Talk to some scientists and you'll be told that the genus Homois little more than 100,000 years old and excludes even the most famous prehistoric "humans", the Neanderthals. But others say our human genus actually has a history stretching back about 11 million years old and includes not only living people and extinct Neanderthals, but also chimpanzees and even gorillas.

How can there be so much disagreement on such a fundamental issue? And, more importantly, which definition of the human genus is the right one?

"That's the $64,000 question," says Jeffrey Schwartz at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, US.

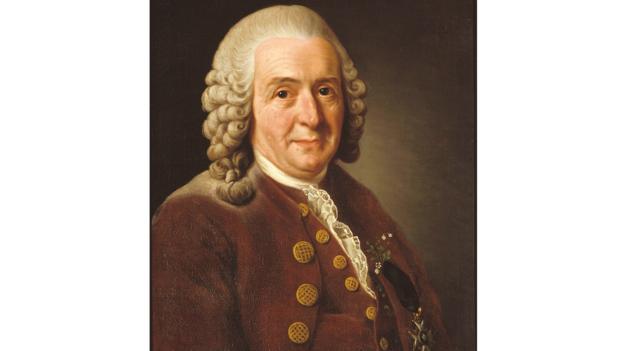

The problem arguably begins with the 18th-century biologist Carl Linnaeus, who was the first to standardise the way species and genera are named and defined. He named thousands of species in his seminal 1735 book Systema Naturae, but when it came to our genus, he got a bit metaphysical.

The basic wisdom is that brain size got bigger

When he named each animal genus, Linnaeus carefully noted its defining physical features. But under Homo he simply wrote "nosce te ipsum": a Latin phrase meaning "know thyself".

Perhaps Linnaeus thought humans were so obviously different from other animals that a formal physical definition was unnecessary. Or perhaps he was referring to the fact that humans are the only animals with the self-awareness to appreciate their own existence.

Either way, his choice of words implied that humans are fundamentally different from everything else.

It is an understandable mistake: he was working over a century before the publication of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, which made it clear that humans are a part of the animal kingdom. But researchers like Schwartz argue that Linnaeus's decision may help explain why the human genus continues to be so difficult to define.

Many of the scientists who study human evolution would actually deny there is a problem defining the human genus. They say that humans first appeared in Africa between 2 and 3 million years ago.

When he named each animal genus, Linnaeus carefully noted its defining physical features

Before then, the continent was populated by a group of "almost humans" that mostly fall into adifferent genus calledAustralopithecus. These australopiths shared some of our features – most obviously, they walked upright on two legs like we do – but their brains were much smaller than ours, and their arms were longer and apparently adapted to climbing in trees like other apes. Their diets also differed from ours.

"The basic wisdom is that brain size got bigger, hominins started to eat meat, they started to have body proportions that were more modern human like – and that's Homo," saysBernard Wood of George Washington University in Washington, DC, US.

But this conventional definition is not necessarily correct.

The earliest species generally put in the genus Homo actually retain a number of australopith-like features. For instance,Homo rudolfensis lived about 2 million years ago: it had a large, broad, ape-like face rather than a relatively small and narrow human one.

At some point, our ancestors branched away from the australopiths

And while it once seemed that brain size expanded rapidly with the dawn of real humans, more thorough analyses now suggest the change was much more gradual. In other words, what was once a nice clear boundary between the first humans and their australopith ancestors has become muddy.

This is exactly what we should expect, says Brian Villmoare at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas in the US. He says our conventional picture of the dawn of the human genus needs a slight modification. It is far too subjective to look at the fossils and try to judge when they began looking enough like "us" to merit being called human.

Instead, we should define the human genus by looking at our evolutionary tree.

At some point, our ancestors branched away from the australopiths. The genus Homo begins with this evolutionary branching event: physical features like large brains came later, after tens of thousands of years of human evolution.

Australopiths had long arms and apparently spent a lot of their time climbing in trees

The earliest humans were so closely related to the australopiths that they must have looked virtually identical, says Villmoare: small brains, long arms and all. It did not take very long for humans to evolve their own unique features, but the first physical differences between humans and australopiths were so subtle that only a trained eye can recognise them.

Villmoare has such an eye. In 2015, he and his colleagues announced the discovery of what they say is the earliest known fossil evidence of the human genus: a 2.8-million-year-old fragment of jawbone.

What made it human, they say, are a handful of tiny details. For instance, the shape of a small hole in the bone – through which blood vessels and nerves once passed – is unmistakably human-like rather than australopith-like.

If we really want to put our finger on the physical features that define the human genus, arguably it is these tiny details we should point to, rather than focusing on more obvious hallmarks like our large brains.

But not everyone agrees.

For instance, Wood insists that the human genus begins later, when our ancestors evolved a human-like way of life that was clearly distinct from the way the australopiths lived.

It's time we kicked both habilis and rudolfensis out of our genus

Australopiths had long arms and apparently spent a lot of their time climbing in trees. In contrast, we generally live on the ground and have relatively shorter arms. Australopiths also seem to have matured relatively quickly, like living apes, whereas modern humans typically have long childhoods.

Wood says the human genus began when our ancestors finally turned their backs on the trees, and when childhoods began to lengthen. If he's right, it is these adaptive features – as much as anything in our physical anatomy – that we should use to define our genus.

Again, there are implications for the conventional picture of human evolution.

Villmoare and his colleagues did not name the species that their 2.8-million-year-old jawbone belonged to. But the accepted picture is that by about 2 million years ago the Homogenus had given rise to at least three human species – H.habilis, H. rudolfensis and H. erectus. Wood says that, of the three, only H. erectus deserves a place in the human genus.

Its life history was significantly different from modern humans

"What little we know about the life history [growth rate] of habilis andrudolfensis suggests they were not significantly different to the australopiths," he says. What's more, careful study of the fossils suggests H. habilis retained an australopith-like ability to climb in trees.

It's time we kicked both habilis and rudolfensis out of our genus, says Wood. At least for the moment, they should probably be lumped with the australopiths.

The trouble with this approach is that human evolution studies keep uncovering facts that muddy the issue even further.

No one doubts that Homo erectus had body proportions rather like ours and spent most of its time walking on the ground, rather than climbing in trees. But in 2001 we learned that itprobably matured at a much younger age than we typically do. "Its life history was significantly different from modern humans," says Wood.

They found that the typical primate genus is between 11 and 7 million years old

So do we throw H. erectus out of our genus too? Or do we tweak the definition of humanity again, to allow this iconic species to retain its human status?

Wood favours this second option, but it too has implications. "If you want to include erectus then you have to say Homo includes organisms with a range of life histories. It's not something they have in common," he says.

Perhaps it would be better to take a completely different approach to defining humanity.

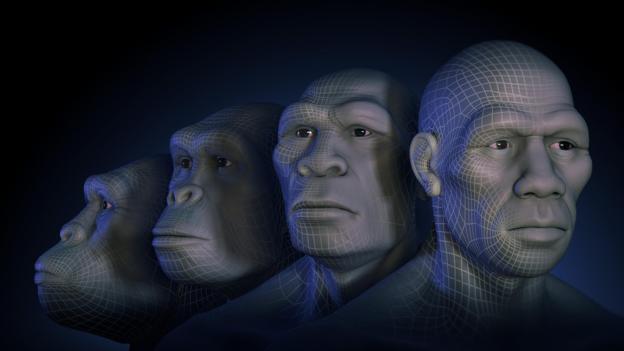

In the late 1990s, a team of biologists broadened the debate bylooking at the way genera have been defined across the whole primate family tree. They used rates of genetic mutation, and information about the degree of genetic variability in each genus, to calculate when the various genera first evolved.

Chimpanzees belong in the human genus

They found that the typical primate genus is between 11 and 7 million years old. This makes Homo, supposedly about 2.8 million years old, a remarkable exception.

The researchers said it would make sense to bring our genus in line with the rest of the primates, by tripling the length of its history. In other words, it might be simply duration of existence – not anatomical features or behaviour – that defines the dawn of the human genus.

But this approach leads to a striking result. If the first members of the genus Homo lived 11 million years ago, then their living descendants include not only all of humanity, but also the chimpanzees, because the chimpanzee lineage branched away from ours only 7 million years ago. Chimpanzees belong in the human genus.

This sounds controversial, but a number of scientists have concluded that it makes sense. In 2001, one team of geneticists took an even broader approach to the human genus question. They looked at the range of genetic variability in a number of mammalian genera.

Humans and chimpanzees, famously, share as much as 99% of their DNA in common, depending how you measure it, with gorilla DNA only marginally more distinct. Species of cats, dogs or bears with this level of genetic similarity would be put in the same genus, and apes should be no different. So not only do chimpanzees deserve a place in the human genus, using this genetic definition gorillas should be included too.

I no longer regard chimps to belong in Homo

This idea has also received support. In 2003 Darren Curnoe, now at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, working with the late Alan Thorne, used DNA to re-evaluate the way our extinct ancestors are named and defined.

Curnoe and Thorne pointed out that humans and chimps look very different despite sharing almost their entire DNA in common. This suggests apes evolve physically distinct features very easily, even if their genes remain similar.

The pair suggested we should avoid naming new fossil hominin species or genera simply on the basis of small differences in the physical appearance of their bones. All human-like fossils stretching back at least 7 million years belong to the genusHomo, they said – and the genus should also include chimpanzees.

However, Curnoe says he has since changed his mind.

"I no longer regard chimps to belong in Homo," says Curnoe. He is now a champion of the picture painted by researchers like Villmoare. Namely, humans first appeared about 2.8 million years ago with species like H. habilis and another – H.gautengensis – that Curnoe described from South African fossils in 2010.

Although Curnoe disagrees with his earlier conclusions, they were at least an attempt to bring the definition of the human genus in line with the way other primate and mammalian genera are defined – and move away from the unusual definition Linnaeus gave us 280 years ago. Wood says this is what he is striving to do too with his preferred definition ofHomo.

We have to treat hominins as we would treat any other organism

Schwartz also wants to bring the definition of Homo into line with the rest of the mammal genera. But his way of doing so leads to another dramatically different result.

Schwartz believes that physical features, not genes or behaviour, are the single most important way to distinguish between mammalian genera.

"Otters use stones to open shells, crows can use pebbles to raise the level of water in a tube so they can drink, [but] we wouldn't use those behaviours to define otters or crows," he says. "We have to treat hominins as we would treat any other organism."

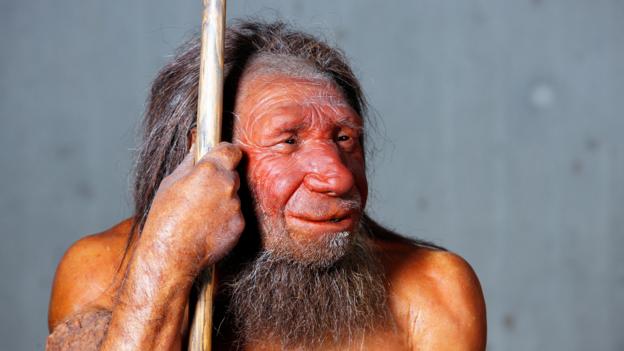

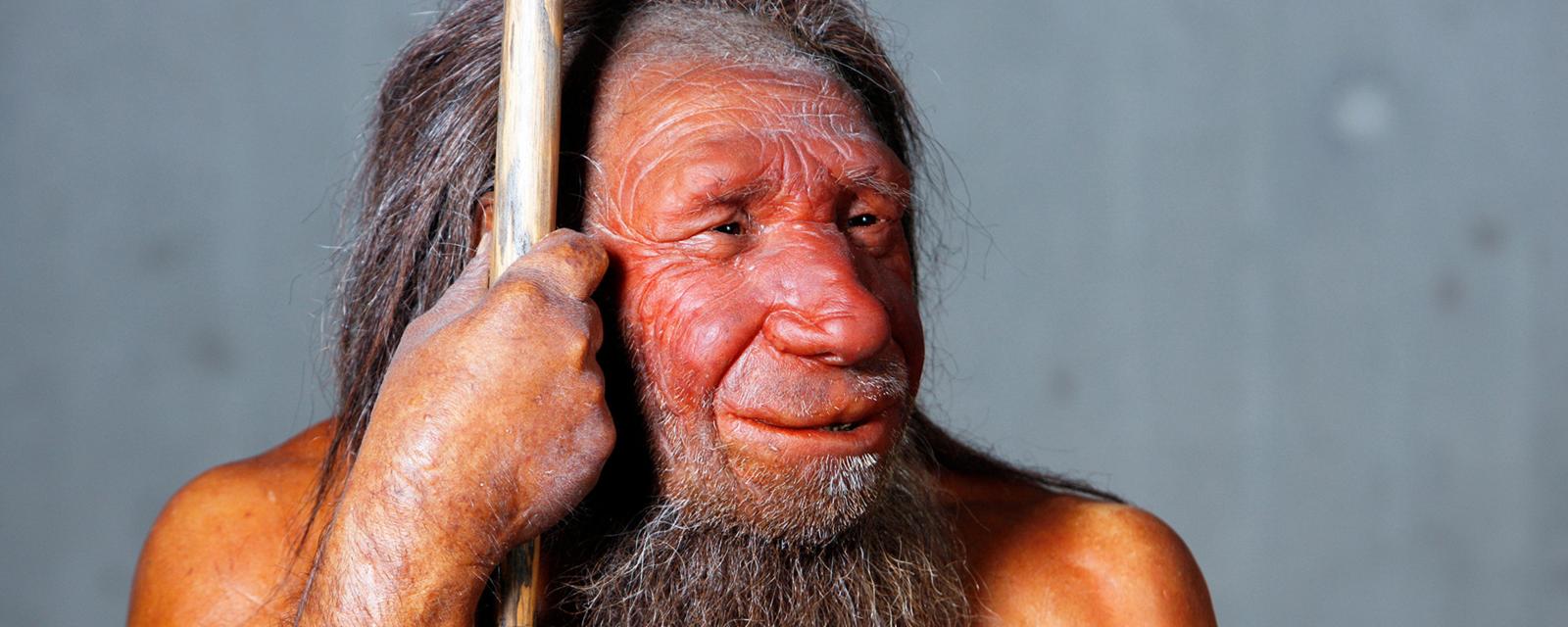

If you look closely at hominin fossils, Schwartz says, you will find there is a lot more variability than most researchers appreciate. For instance, the Neanderthals were stouter than we are, with prominent brow ridges that we typically lack.

Schwartz says that, in any other kind of mammal, those sorts of differences would lead biologists to put the two species in completely different genera. Never mind debating the merits of including chimpanzees in the human genus: Schwartz says we should think hard about whether Neanderthals, our extinct "cousins", really belong there.

There is no shortage of possible scientific definitions we could legitimately apply to our genus

He says we should start with what we know – living humans – and work slowly back through time, evaluating which fossils really belong in our genus and species. "It's not popular, but if we want to treat hominins in the same way we treat pigs, rodents, horses and other mammals it's what we have to do."

He has already begun using this approach, focusing on hominin skulls and jaws. It is things like the shape of our chin and our brow that define the human genus, he says. These features probably only appeared on Earth about 100,000 years ago.

That means a handful of fossils from sites like the Skhul Cave in Israel and the Border Cave in Southern Africa belong with living people in the genus Homo, but little else does.

Clearly, there is no shortage of possible scientific definitions we could legitimately apply to our genus. But there is no consensus about which definition is the right one, and given how strongly opinions vary, it seems unlikely that the issue is going to be resolved in the near future.

It might seem surprising that we struggle to define the very thing we are. But perhaps it is exactly because this debate centres on humanity that consensus is so hard to find.

"No one gets crazy if we look at fossil horses in a comparative way," says Schwartz. "Because it's hominins, people get emotional."

Which species should be classified as Humans?

![]() Reviewed by Unknown

on

1:38:00 AM

Rating:

Reviewed by Unknown

on

1:38:00 AM

Rating: